Ending the candlelight vigils

Recent suicide in Kansas City spark discussions about suicide prevention

February 7, 2018

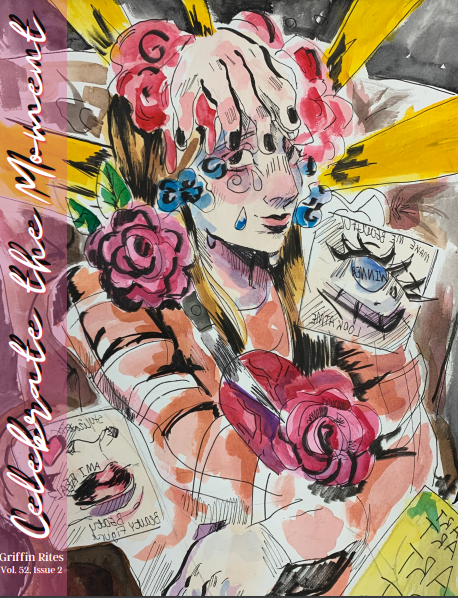

A candle burns as a symbol of the candlelight vigils that are often held after suicide deaths.

Kansas city and candlelight vigils

“I believe in you.” “You are important.” “Everyone matters.”

On the sidewalk outside of Shawnee Mission Northwest High School, these are the messages on the signs held by students and parents.

It is Jan. 25, a cold morning. The sign holders wear coats, gloves and hats in the wind. The trees are bare. The sun is just beginning to rise in the dark blue sky. One day earlier, the school lost one of its own students to suicide. Two days before that, they had lost another.

These are not the first suicide deaths in the Kansas City area. In March 2017, two Belton students died from suicide just days apart. In September, it was 17-year-old Gamesha Thomas, a student at Lee’s Summit North, that lost her life. Both communities held candlelight vigils in the days following student deaths. Wax melted on concrete sidewalks and rose-lined picture frames; they called it memoriam.

Just over a month ago, on Dec. 15, junior Carli Crum attempted to take her own life.

“I just hit rock bottom,” Carli said. “I’m a perfectionist so I’m always putting pressure on myself to just be the best. I don’t like to fail so I don’t want to talk to anybody or reach out to anybody because then it feels like I’m failing or I’m going to fall off.”

A taboo topic

According to the Center for Disease Control, suicide rates among teens have been steadily increasing for more than a decade. Since 2007, the rate of suicide among girls ages 15 to 19 has doubled. The suicide rate over the same time period for boys of the same age increased by 30 percent.

In 2004, Chad McCord of St.Louis was one of the many victims of suicide. As a result, his mother Marian McCord co-founded the CHADS [Communities Healing Adolescent Depression and Suicide] coalition, a non-profit organization where she currently serves as the executive director.

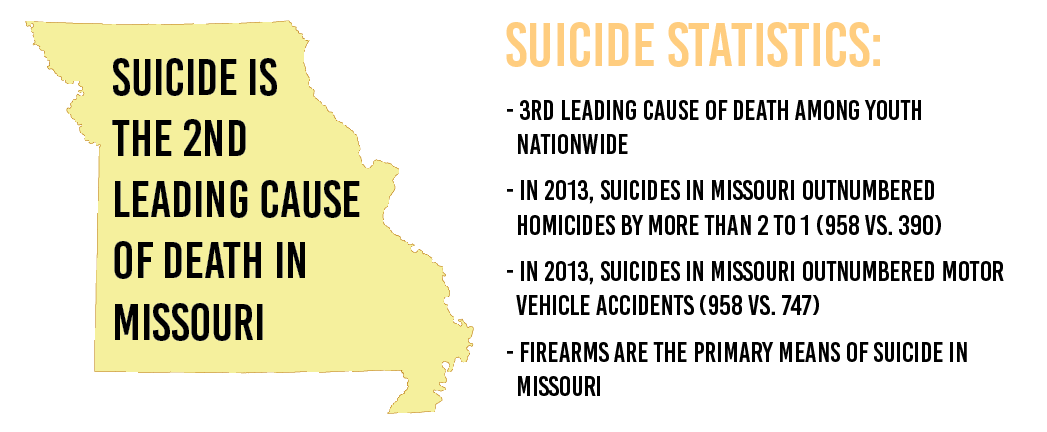

“Our society is not ready to look at how big this problem is and the number of lives mental illness is taking,” McCord said. “In spite of suicide being the second leading cause of death among our teens, we as a society have invested so very poorly in prevention and better treatment options.”

One of the problems with the way suicide is handled revolves around the way mental illness is viewed, according to McCord, who emphasizes that mental illness is a real physical ailment.

In recent years, campaigns for the visibility of mental health and suicide have increased awareness about it in the general public. On April 28, 2017 popular musicians Alessia Cara, Khalid and Logic dropped the now grammy-nominated joint song entitled ‘1-800-273-8255,’ the number of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL), which discussed the topic of teen suicide.

“I just felt that it [suicide] was something that is so important but that no one really wants to talk about, especially in the mainstream media,” Cara said in an interview on “The Ellen Show.” “It’s always this taboo, touchy subject but this is real and there are so many people who have gone through this, even people close to me, who have felt that their lives aren’t worth it just being who they simply are, and I just thought this would be a great opportunity to talk about that and to let people know that they aren’t alone.”

The day after the song was released, the NSPL received their second highest call volume on record according to its director John Draper. By August, traffic to the hotline had increased by 33 percent from the same time last year. This enabling of discussion is, according to McCord, life saving.

“Many people think about suicide, and when people talk about suicide it opens the door for the person that had been thinking about it to actually talk about it,” McCord said. “Anytime you can get someone to talk about their thoughts of suicide, you could be saving a life.”

Despite the proven power of discourse, the topic of suicide remains somewhat taboo in most regions, with little action taken to genuinely increase discussion of mental illness.

“There are students in your school right now considering suicide. By not allowing the opportunity to talk about suicide, we are not giving those students enough opportunity to ask for help,” McCord said. “Generally speaking, the fact that we do not want to talk about suicide and therefore will not talk about it, is in reality very harmful. We should be talking much more openly about suicide. By not talking about it, it adds layers of misunderstanding, shame and guilt.”

Sophomore Cozmo Crum, Carli’s brother, has watched his sister’s battle with depression over the years, and he has come to believe that the best way to prevent suicide and mental illness is to be open to understanding those who struggle with it.

“Sometimes I feel like it’s hard because people don’t want to admit that they’re not happy or that they’re going through something tough because they want to make others happy around them,” Cozmo said. “Talking about it more often will make it less taboo so that more people can understand it, and understanding is what we all need. I think talking about it, not having an assembly, but people in general being more open about it, will help. It’s hard to just be open about it but if someone needs help they should be able to go to anyone.”

Seeking help

After her suicide attempt, Carli sought help at the Two Rivers Psychiatric Hospital in Raytown, MO.

“Being in the psychiatric hospital, I had a week to focus on myself,” Carli said. “You get really caught up in your schoolwork and focusing on your grades and being with friends and doing all of this stuff and you forget to take the time to just relax and be happy with your own self. [At Two Rivers] I didn’t have my phone. It was just me and my recovery and being around kids that were going through similar stuff.”

Now back at school, Carli said that she is learning to prioritize her mental health over her other activities.

“I think what helped a lot is that a lot of my teachers and my counselors know what happened,” Carli said. “Mrs. Ford [counselor Jennifer Ford] told me that I could go to her office if I ever needed a break or anything. I think it’s good to have people around you that know and be able to reach out to them so that you can have them in those hard times and have the resources to be able to take a break because the most important thing is to be able to focus on yourself.”

While self-focus can be challenging, a pivotal step for Carli is finding people and places where it is safe for her to speak out about personal problems.

“I feel like it’s [speaking out] important because in the moment it’s such a hard thing to overcome but it’s a good thing to get those feelings out so that they don’t come back and they’re not just circulating around in your head,” Carli said. “When they build up that’s when it gets bad and that’s when it all starts to crumble.”

Whether it is seeking solitude in a counselor’s office, or taking the liberty to forego school and social events, Carli speaks from personal experience when she advises students to take time to themselves and to ask for help.

“I think listening is really important and kids need to know that it’s okay to take the pressure off of themselves and take a break if they need to,” Carli said. “Just have time to focus on themselves without worrying about everything on their plate. They need to feel okay to speak up and say ‘Hey, I don’t think I can do this. I need help.’”

Proactive policy

With the rise in suicides, signs and candlelight vigils, a new Missouri law was passed in December 2017 that requires schools to have a suicide prevention policy in place by July of 2018, along with support for faculty suicide prevention training.

“I would highly recommend an evidenced-based suicide prevention program such as SOS Signs of Suicide for students, teachers and administration,” McCord said. “I also encourage your school to start an Ambassador Club; a club that focuses on promoting positive and encouraging mental health messaging in your school. It also equips students to help be that special friend to those that struggle with mental health.”

Although there is no official plan in place yet for the North Kansas City School District, school and community resource officer Shelly Meinke confirmed that steps are being taken to address student mental health concerns. Until a new plan takes effect, Meinke recommends that students become familiar with the signs of suicide and become more comfortable speaking about it with friends and staff.

“A great way to be proactive is to know the warning signs that may possibly indicate if someone is struggling,” Meinke said. “Often, a person dealing with overwhelming feelings will talk about or discuss things like: wanting to die, being a burden to others, feeling hopeless or trapped or being in constant emotional or physical pain. If you notice any of these warning signs, talk to the person you are concerned about, let them know you care. Ask if they are thinking about harming themselves. Seek help: let someone – counselor, teacher, parent – know immediately about the situation.”

In December, student council hosted a mental health awareness week. Each day the halls turned yellow, blue, green or another color representing different mental illnesses. It was an almost silent show of support for those who are struggling, and for Carli, it made an impact.

“I think that it’s [showing support for students] important because it helps students know that they’re not alone,” Carli said. “I think the best thing to do is to know that you’re not the only one out there. That’s why I’m so open about it because I want people to know that it gets better.”

The signs outside of Shawnee Mission Northwest are now gone, and so are the wax remains of candles outside of Belton, Lee’s Summit North and Olathe West, but here at Winnetonka there remains a community of support for those who need it.

“You are not alone,” Meinke said. “We are here to help.”

A candle smokes after having just been blown out representing a possible end to the teen suicides.