This land is our land

Immigrants share their stories, struggles and successes

January 4, 2018

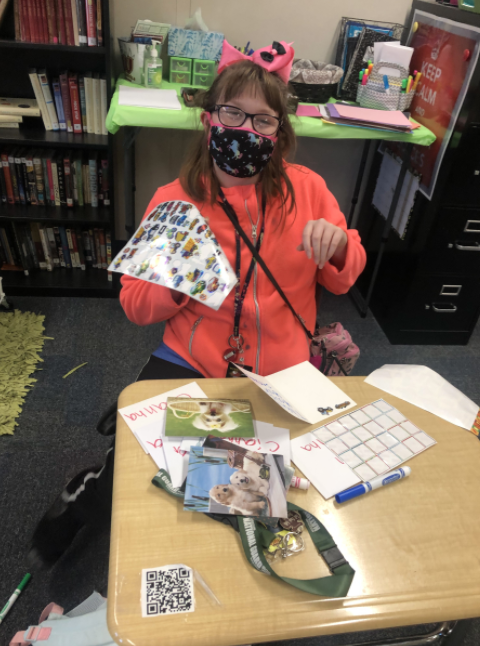

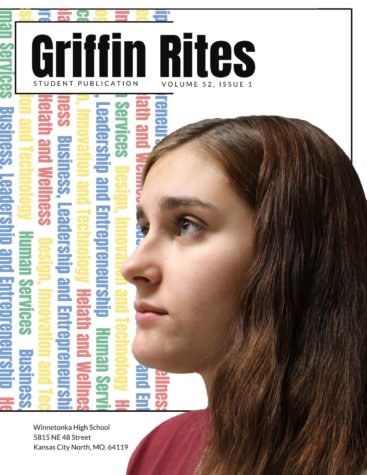

Senior Lily Abdulla stands at the homecoming game on Sep. 29 where she was a member of the homecoming court.

Foreign-born immigrants make up 13.5 percent of America’s population according to the 2016 Current Population Survey. These over 43.3 million people and their 41 million American born children come from around the world, bringing with them hundreds of different cultural traditions.

Raised in America but born in South Sudan, senior Lily Abdulla’s childhood is one marked with change and movement. She left her birth country when she was just 3 years old.

“My grandmother was like my mom, we were always together. She took care of me all the time, she was always there for me,” Abdulla said. “I remember this one day we [Abdulla and her mother] got on a train and we never went back. I cried. I bawled all of my tears out and got sick. I was so upset because that was the last time I ever got to see her [grandmother]. I miss her so much.”

Nearly 1 in 5 women in South Sudan give birth to their first child before they are 18 years old according to UNICEF. Abdulla’s mother gave birth to Abdulla at the age of 17, and no woman in her family has graduated high school. Three years after Abdulla was born, her mother made the decision to leave South Sudan and travel to Egypt in order to provide her daughter and any future children a better education.

“My mom had me when she was as old as I am right now, and a lot of other girls in South Sudan do that too which is one of the things that is stopping them from going to school and getting an education,” Abdulla said. “If you do want to get educated there, then your parents usually send you away to a family member who lives in a better place in Africa or to America. My parents didn’t send me away, we all came together as a family.”

After living in Egypt for two years, Abdulla and her family immigrated to America.

“On the plane here, that was the first time I tasted pizza and hamburger. My parents had to sit with my little sister, so I was alone, but it was crazy,” Abdulla said. “I mean, New York, Ellis Island, all of that is like freedom. Once you’ve past it, you’re free.”

Abdulla and her family stayed in New York City for two days before moving to downtown Kansas City. No one in the family besides Abdulla’s father could speak English.

“The first few days and months were horrible because we didn’t know how to do anything,” Abdulla said. “When I went to school I didn’t know English or anything so I felt dumb because people would talk and I would just sit there. I would speak in my own language [Arabic] like they knew what I was talking about.”

Two years later, Abdulla moved one last time to North Kansas City where she still lives with her mother, step father, younger sister and two younger brothers. Although she began American school at the age of 7, Abdulla said she sometimes still struggles with speaking.

“I get frustrated sometimes because I think in a very different way than other people,” Abdulla said. “When they say something I take it to my head as something else. I think of the order of words in a different way, so when people say something it can take me a while to understand what they mean because I have to rearrange their words so that they make sense to me. Others don’t really understand that. I get frustrated when people don’t understand me because I feel dumb and like I can’t do anything.”

Part of Abdulla’s struggle with English comes from learning two languages at once. Abdulla’s mother taught her and her sisters to speak Arabic at the same time that they were learning English, and it is still spoken frequently in their household. Senior Waleed Khaleel also speaks Arabic since he immigrated to America from Jordan in the seventh grade.

“We [Khaleel and his family] wanted to live the American dream just like everybody else,” Khaleel said. “The economy is bad in Jordan so America is like a second chance for us to start a new life. I am definitely happy that I came here, but sometimes you do miss the people back home.”

According to Khaleel, although America is often viewed as a safer nation than third world countries, it does not always feel that way.

“It [Jordan] just feels safer, even though it’s not the safest place in the world. You can go out at 3 a.m. as a male or a female on a walk and feel safer than taking the trash out at 12 a.m. here,” Khaleel said. “The people there are friendly. They don’t ignore you like here.”

Although he sometimes misses Jordan, Khaleel said that he enjoys America’s diversity, even though he believes it can be hard to get to know people so as to appreciate that diversity.

“My favorite part of America is the difference in cultures,” Khaleel said. “You can meet people from all around the world. You can learn a lot from hanging out with people with different backgrounds. But sometimes you feel isolated from your community. People don’t even know their neighbor’s name, which is really sad.”

But despite the cultural diversity of America, some citizens do not accept immigrants like Khaleel and Abdulla.

“I hate when people say ‘go back home,’ because I can’t. I can’t because there is civil war in my home,” Abdulla said. “Since colonialism, African countries have become so corrupt over power and who gets what and I don’t want America to be dividing people too. We should all be one. We shouldn’t be talking down to people just because they are different.”

In 2015, 1.38 million foreign born individuals moved to America according to the Migration Policy Institute. Khaleel hopes that people will learn to ask questions and understand that these immigrants are just as American as natural born citizens.

“Home will always be home, but America is my new home now,” Khaleel said. “It is definitely disappointing when people say it [negative things about immigrants], because most of the time people’s hate towards immigrants is based off of ignorance, but a lot of people are not that way. Don’t be afraid to learn. Always ask, if anything is going through your head, if you ask respectfully then even though it might come off as a little offensive I am sure the person that you are asking will still be understanding.”

Though she may have a different heritage than the average American citizen, Abdulla grew up in the United States and believes that it has played a crucial role in creating her current character.

“If I wasn’t here I wouldn’t be who I am,” Abdulla said. “I think that when people are against immigrants, when they say that we’re bad, well no, we just want an opportunity. Isn’t America called the land of opportunity? We came here because we wanted a better life, that is what this nation promises.”

Americans may come from all around the world, but it is their ancestral and cultural differences that Abdulla believes unifies them.

“Truly, we are all immigrants. You came here, or someone in your family did, and even if you just came from Alabama instead of Africa, you are still not from here, from this community,” Abdulla said. “We are all foreigners, that is what we have most in common. I am from South Sudan. I was born there. But I came to America and I was raised here. They are both my homes.”