A new net

The two sides of net neutrality

February 15, 2018

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted to end net neutrality on Dec. 14, 2017, a law put in place in 2015 to ensure internet equality. While the FCC assured Americans that the repeal of net neutrality was to increase competition among companies to drive internet costs down, many citizens are concerned about the lack of regulation after the repeal.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted to end net neutrality on Dec. 14, 2017, a law put in place in 2015 to ensure internet equality. While the FCC assured Americans that the repeal of net neutrality was to increase competition among companies to drive internet costs down, many citizens are concerned about the lack of regulation after the repeal.

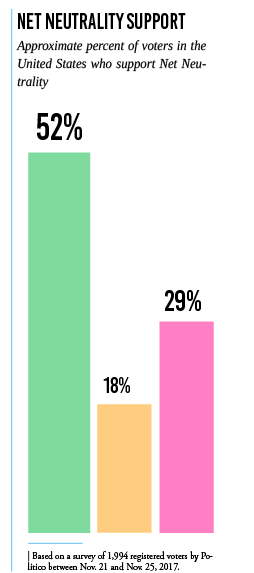

The decision to repeal net neutrality came after weeks of public protest both on the streets and on social media. In a survey by the University of Delaware’s Center for Political Communication, which was released approximately one month before the FCC vote, 81 percent of Americans opposed the repeal of net neutrality. History teacher Ian Johnston was one of the majority of Americans in support of net neutrality.

“This [the repeal] is completely against what the people want,” Johnston said. “Net neutrality is basically free and open access to the internet without having corporations of ISPs [internet service providers] limiting or throttling speeds. [With net neutrality] corporations are under certain rules that they have to abide by for internet protections by the consumer. The majority of people do no want it repealed, but they’re going ahead and not listening to the people although that’s what the government is for.”

After the vote to repeal net neutrality, FCC chairman Ajit Pai addressed this public concern in an oral statement where Pai stated that the belief that Americans will have to begin paying for all internet services is incorrect.

“Following today’s [Dec. 14, 2017] vote, Americans will still be able to access the websites they want to visit,” Pai said. “They will still be able to enjoy the services they want to enjoy. There will still be cops on the beat guarding a free and open internet. This is the way things were prior to 2015, and this is the way they will be once again.”

According to Pai, repealing net neutrality will create more competition – not less – among broadband providers and will create a more open internet.

“Broadband providers will have stronger incentives to build networks, especially in unserved areas, and to upgrade networks to gigabit speeds and 5G,” Pai went on to say. “This means there will be more competition among broadband providers. It also means more ways that startups and tech giants alike can deliver applications and content to more users. In short, it’s a freer and more open internet.”

Although increased competition is the intended outcome of the repeal of net neutrality, many critics believe that instead, companies will now be able to charge customers a monthly fee for access to certain internet sites and services.

“The change [repeal] does open the door for ISPs to charge more to some big broadband users, say Netflix or YouTube, which could pass those increased costs to their subscribers,” Mike Snider and Jefferson Graham wrote in the USA Today. “In theory, ISPs could charge subscribers more, too.”

According to senior Kyle Hayden, if ISPs charge subscribers more, the new internet policy may be an issue for students, since the North Kansas City School District may opt for smaller internet packages to keep costs low.

“The school has to provide us with internet so that we can accomplish the things we’re here to do,” Hayden said. “Personally, I’m foreseeing us having a lot less access to the sites that we need to use and the sites that we want to use.”

Whether the repeal of net neutrality will drive internet costs up or down has yet to be seen. However, with 22 states suing to block the FCC’s repeal as of Jan. 17 according to the Los Angeles Times, it is unlikely that Americans will feel the effects of the repeal in the near future.